Power surge

International companies are readying to buy up parts of the electric production, distribution and transport of energy, as Magda Galbau finds what is left to sell International companies are readying to buy up parts of the electric production, distribution and transport of energy, as Magda Galbau finds what is left to sell

In the electricity sector, distributors are halfway through privatisation, while none of the nuclear, coal-fired or hydroelectric producers are in private hands.

But with the liberalisation of the European energy market in full swing, market forces will have an effect on the price of electricity.

If Romania does not set up efficient production mechanisms, then distributors could bring in cheaper energy from abroad.

However, due to its variety in energy-generating systems and cheap running costs, Romania could also be in a position to export energy.

Analysts expect that shortly, prices of electricity in Romania could rise for consumers to align with Europe. Prices in Romania at the moment are cheap compared to those in the EU.

Four of Romania's eight distributors are now in private ownership, while the producers and Transelectrica, the firm which takes the electricity from the producers to the eight distributors, remain part of the state. Around two thirds of energy is now in a regulated market, with one third in a competitive market, according to state firm Electrica.

This has been quite a slow privatisation process. Some of the difficulties for the Romanian state in attracting investors are due to investors' desire to gain a fast return, which does not always happen with utilities. Such investors also expect, owing to the impending liberalisation of the Romanian energy market, a lot of competition from abroad. Because of EU policies in cutting back on state aid, the limit of state loans to subsidise the industry is also too low for some investors.

State distribution company Electrica must sell its four remaining branches in the next couple of years. These are Muntenia Sud, by the end of 2005 or beginning of 2006, Transilvania Sud and Transilvania Nord at the end of 2006, leaving only Muntenia Nord. So far the market is 55 per cent opened in terms of energy supply, thus very competitive, say Electrica officials. This state company has one maintenance firm with exclusive rights for repairs until 2007, which Electrica says “is very competitive”. This is not on contract, but through what seems to be an understanding between the two parties. Therefore Electrica is preparing a task book so that distribution branches can participate in auctions for such maintenance services.

Going nuclear

Nuclear electricity looks to be on the increase in Romania as its one giant power station increases production with a second unit due to open, plans for a third, and a market open to exports in 2006.

This year the firm will start delivering electricity directly to consumers.

Romania decided to construct a nuclear power plant in the 1980s, when the Communist Government used the Canadian technology CANDU (Canadian Deuterium Uranium) to build a unit at Cernavoda, on the Danube near Constanta. This was a project to build five reactors at the same time and led to many delays and missed targets. Before the opening of Cernavoda, the firm decided to make only one reactor active and conserve the remaining four for another time.

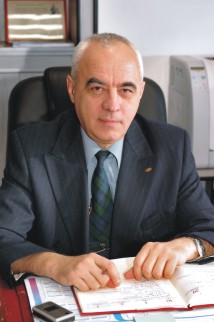

“Its only active unit provides approximately ten per cent of Romania's necessary electricity, with a production capacity of 88 per cent and by 2007 we expect the first unit to cover around 18 per cent of the country's necessary electricity,” says Teodor Minodor Chirica, general manager of state-owned Nuclearelectrica, the energy firm that runs Cernavoda. The Unit 1 produces over five million Megawatts hour/year of electricity.

“Starting on 1 July, we will deliver directly on the Romanian market rather than through Electrica, and we are looking for large corporations to act as partners,” says Chirica. In 2006 the firm will have access to export energy.

Concerns over leakages are so far few, as the impact of the radiation on environment is below one per cent of the maximum admitted by law, adds the general manager.

Power generation firm from Italy Ansaldo Energia has been in Romania for over 25 year and acted as general contractor in setting up the nuclear plant. From its five units, Ansaldo, together with Canadian firm AECL, has contributed to completing the first unit, setting up the second and finalising the pre-feasibility study for the third.

“Unit One and Two from Cernavoda will allow Romania to reduce its orders for classic fuel imports by 300 million Euro a year,” said Giovanni Villabruna, director Ansaldo Energia Romania. “This is possible only because all the elements in the functioning chain of nuclear installations are easy to be found and produced in Romania.”

The current building of the Unit Two offers jobs to over 5,000 people, and an estimated turnover exceeding 100 million Euro a year. Ansaldo is also interested in building new classic electrical power plants in Romania and in revamping the existent ones, says Villabruna.

Going hydroelectric

Accounting for 31.6 per cent of generated electricity, state-owned hydroelectric firm Hidroelectrica has an estate of 350 hydropower plants and power pumping stations. The grandest construction is the Yugoslavian-Romanian Portile de Fier (Irongate I and II), a power plant that siphons off energy from a narrow channel of the Danube and supplies energy to Serbia and Montenegro and Romania, whose states remain its co-owners.

The Government initiated the privatisation process of 21 hydropower units in 2001 and companies interested include Italy's Enel Produzione, Romania's Neptun SA, Montizola (Czech Republic) and Mecamidi (France).

In 2003 the state began to privatise 54 micro-hydro power-plants in Hidroelectrica's estate. A micro hydropower plant has a capacity of up to 100 kilowatts and its system can produce enough electricity for a village. According to Hidroelectrica, these plants represent the future of power for SMEs in rural tourism and in supplying energy to remote areas.

The Institute for Hydro-energetic Studies and Projects from Romania, Energy Holding and Italian ESPE bought 18 of these plants last year, paying the state 670,000 Euro in total. In 2002, according to a Government decision, Hidroelectrica took over 237 more of these plants from Termoelectrica and Electrica. The Ministry of Economy and Commerce aims to sell 150 micro-hydropower plants by 2007.

Going thermoelectric

Among the producers, thermoelectric power accounts for 37.6 per cent of Romania's energy and three large power plants exist in Romania.

“We are working on accelerating the [privatisation] process of Termoelectrica, but we are not certain when exactly it will be completed,” the company general director of Termoelectrica Ovidiu Pop tells The Diplomat. “The process depends primarily on the interest which each power plant presents to potential investors.”

Pop says a regional electric market will happen in Romania.

“For real competition, we believe a reconsideration of grouping the electrical energy producers is necessary,” says Pop. This, he says, will be “an intermediary step” to accomplishing a pan-European energy market.

The reasons for Romania's tardy privatisation has come down to several political and economic factors, argues Pop.

Investors consider it necessary that the Government privatises electricity distribution companies first. The global increase of prices in natural gas and crude oil has led to decreasing attractiveness for investors in setting up new thermoelectric power units. Costs of modernising existing coal power stations or building new ones, as well as the money needed to protect the environment under European legislation are also factors which can deter investors.

Pop believes the Government could attract investors by setting up thermo-hydroelectric mixed entities, so that when the raw materials for coal-fired power stations are not available at good prices, the mixed entity can produce energy using water, and vice versa.

The buyers

Czech power firm CEZ is a producer and seller of electricity with an aim to become a regional leader in eastern Europe. The firm already has three distribution companies in Bulgaria and has bought one of Romania's eight local electricity distribution companies, Electrica Oltenia. This seems to be the first step towards moving into the production of energy. Czech power firm CEZ is a producer and seller of electricity with an aim to become a regional leader in eastern Europe. The firm already has three distribution companies in Bulgaria and has bought one of Romania's eight local electricity distribution companies, Electrica Oltenia. This seems to be the first step towards moving into the production of energy.

“We are interested in other opportunities on the electro-energetic market in Romania, it depends on how gradually they will appear and how valuable these acquisitions will be for CEZ,” Ian Veskrna, a CEZ official tells The Diplomat.

The firm says it will “look closer” at the forthcoming tenders for the three thermoelectric power plants Turceni, Craiova and Rovinari and also in the distribution market for the remaining four distribution firms.

“We have had for some time a common history and that is why we have quite a clear idea about what problems Romania has been facing,” adds Veskrna. “We have received an announcement that there is a chance to cooperate in Doicesti [Dambovita county] for a project referring to building a power plant in Romania, but the concrete activities have not started yet.”

Enel is interested in becoming both a player in distribution and power generation, Gianluca Caccialupi, general manager of Enel Servicii tells The Diplomat.

For now, the Italian company is focusing its investment plan on its two electricity distribution purchases, Electrica Banat and Electrica Dobrogea, to gradually increase their network efficiency and replace old equipment.

But its appetite is not yet satisfied.

“Enel is ready to enter the next round of privatisations in the electricity sector starting with the state's sale of the majority stake in Electrica Muntenia Sud and the privatisation of the three coal fired power plants in the Oltenia region. For the near future, Enel is also interested in acquiring hydro-power plants and is evaluating the opportunity to take part in the third unit of the Cernavoda nuclear power plant,” says Caccialupi.

Building up a new thermo, nuclear or hydroelectric power plant in a Greenfield investment could take many years and be more expensive than acquiring an existing asset and investing in its rehabilitation, says the general manager of Enel Servicii.

The Italian company said there is no plan on whether or not to cut back on staff redundancies for Electrica Banat and Dobrogea and no agreement in this respect has ever been discussed with the Romanian authorities.

Supporting trade

Private electricity supplier Energy Holding supplies consultancy services on energy projects and equipment for the rehabilitation of hydropower plants, including an involvement in the rehabilitation of Portile de Fier I and II. The company has ambitions to expand in Romania and the surrounding countries and is looking into opportunities in production and distribution of energy. In production, it is one of the few local firms interested in renewable sources such as wind energy, while in distribution it is supportive of trade exchanges in energy.

Recently the firm has opened a new Energy Management Center for its customers, mainly industrial firms, in a two million Euro investment, which could help facilitate the future trading of energy between national and regional markets.

“This platform enables us to have a real time connection with our customers, suppliers, and also, in the near future, with national and regional energy exchanges,” says Enrique Ferrer, president of Energy Holding.

Transporting energy

National electrical energy transport company Transelectrica aims to allow the safe and stable functioning of the Electro-energetic National System (ENS). This is the 'middle man' between the producers and the distributors. The Romanian electro-energetic system is connected to the western European system of the Union for Coordinating the Electricity (UCET) by electrical lines of 400 kV between Arad, Romania and Sandorfalva, Hungary and Rosiori, Romania and Mukacevo, Ukraine.

“The activity of Transelectrica is a natural monopoly, thus the company currently has no competitors on the market,” says Ion Merfu, general manager of the company. “For 2005, Transelectrica plans to invest 184 million Euro.”

Ambitions include modernising electrical plants Isalnita, Gura Ialomitei, Paroseni, Barbosi, Stejarul, Turnu Severin Est and Minita, building the transport line between Oradea Romania, Nadab Romania and Bekescsaba Hungary and also Nadab-Arad line, between Suceava-Gadalin and Suceava, Romania and Balti, Republic of Moldova. The company will also build a new electric plant for 220 kV at Portile de Fier 2 and an electric line of 220 kV at Portile de Fier 2, Cetate. “For 2005-2007, Transelectrica will invest around 442 million Euro and, between 2008-2014, over 473 million Euro,” says Merfu. Part of the money will be its own investment, while other funds will come from the World Bank, EBRD, European Investment Bank with or without state grants and from PHARE funds.

In March 2005, the Ministry of Economy and Commerce's strategy of accelerating privatisations referred to privatising branches of Transelectrica. In the second half of 2005, ten per cent of Transelectrica's capital share will be listed on the Bucharest Stock Exchange.

Energy's Estate

There are three different forms of electricity producers in Romania: nuclear, hydro and thermoelectricity.

In nuclear energy, Cernavoda has finalised two units and is working on a third unit in an investment worth between 750 and one billion Euro. Seven investors have participated, including LNM Holdings, Enel, Ansalbo, EACL and Curia Hidronuclear Power. There is also the possibility of selling the energy outside of Romania.

In thermoelectricity, there are three “energy complexes” of thermo power plants and coal mines in the west of the country, near Deva. All three, Rovinari, Turcenu and Craiova, are due for privatisation. Groups interested include Washington Group, Siemens, Enercom and CEZ. The power plants that have been decentralised from Termoelectrica and are now under the administration of local and county councils include the branches Deva, Galati, Bucharest, Braila, Borzesti, Doicesti, Paroseni, Drobeta and Govora.

In hydroelectricity, Hidroelectrica has signed a deal with Termoelectrica in exchange for insuring power in the summer months when hydropower plants cannot produce enough electricity. The firm is apparently interested in signing a similar deal with Cernavoda.

There are eight electricity distributors in Romania, each accounting for a large geographical region.

The Government has sold four of these.

Italian group Enel now owns Electrica Banat and Electrica Dobrogea, Czech firm CEZ owns Electrica Oltenia, while German group E.ON owns Electrica Moldova.

Of the remaining distributors, Electrica Muntenia Sud is seen as the most attractive. 61 per cent of this firm is now on sale, the above companies as well as RWE, Electricite de France and Gaz de France have expressed an interest. While in Electrica Muntenia Nord, CEZ and Enel have staked an interest.

Of Electrica Transilvania Nord and Sud, only E.ON so far has indicated their desire for control. This would give the firm the whole northern region, but they must ensure they do not form a monopoly of more than 30 per cent. Gas in transit

Privatisations of the main state gas producer and transit operators are due to start this year, as Anca Pol analyses the proposals Privatisations of the main state gas producer and transit operators are due to start this year, as Anca Pol analyses the proposals

Romania has the largest natural gas market in central Europe and, in this area, was the first country to use natural gas for industrial purposes, according to the National Regulatory Authority in the Natural Gas Sector (ANRGN).

This market reached its high point of activity in the 1980s, as a result of the Communist Party's policy on eliminating its dependence on imports.

This meant an extensive use of internal natural gas resources, which, subsequently, led to the decline of these resources.

For a country which some twenty years ago was proud of its rich Transylvanian natural gas resources, the year 2003, with a total gas consumption of over 18 billion cubic metres, required 30 per cent imported gas from the Russian Federation and only 70 per cent indigenous production.

The main players on the market are the gas producers, even though Romanian gas production is in natural decline. Gas production is cheap in Romania, costing around 60 dollars per cubic metre. Romania's largest producers are SNGN Romgaz SA and SNP Petrom, accompanied by the American companies Amromco Energy and L.LC. New York.

Which is the odd one out? SNGN Romgaz SA, which is the only fully state-owned company. But this will not be the case for long, as the Minister of Economy and Commerce Codrut Seres intends to privatise this gas producer this year.

The Government's Office of State Ownership and Privatisation in Industry has made it public that the privatisation process will be initiated either through selling a majority to a strategic investor (selected by an international financial consultant) or listing the company on the Bucharest Stock Exchange. The company will be put on the stock exchange following an increase in the share capital of the firm by five per cent.

French Gaz de France and German E.ON-Ruhrgas have expressed their interest in participating in the privatisation. It is quite probable that other suitors such as the German Wintershall, Russian Gazprom and Austrian OMV could show up as well.

The dowry of Romgaz is as follows: 116 million USD registered capital, more than 3,600 output wells, 20 compression stations, three underground warehouses for storage of natural gas, 15 dry stations of natural gas, more than 1,900 kilometres of adducting pipes and 1,240 kilometres of collecting pipes, 30 stations for the separation and injection of residual water and 118 injection wells for residual water.

This is a multifunctional system, as Romgaz produces and supplies gas, stores gas, imports the energy source and puts natural gas on the market. The firm also engineers and undertakes geological research into discovering hydrocarbons.

Another firm on the market is the Medias-based gas transporter monopoly, SNTGN Transgaz SA. This company is the operator of the National Transportation System, leased to Transgaz by the National Regulatory Authority in the Natural Gas Sector. The registered capital of Transgaz is of around 27 million Euro.

At the moment, Transgaz also transports gas from the Russian Federation and provides transit for Turkey, Bulgaria, Greece and Macedonia. The privatisation plan of the Ministry of Economy and Commerce differs slightly from that of the gas producer Romgaz: the sale of the majority shares to a foreign utility company and/or the placement on the Bucharest Stock Exchange of five per cent of the registered capital. The listing of Transgaz on the Bucharest Stock Exchange has already begun.

Other specialists may find this move quite odd, as, according to the recommendation of the European Commission, the European model in the field is to maintain gas transportation companies in state ownership. Either way, transparent privatisation seems to always have a positive effect on gas consumers.

“With a bad sector management, the consumer price of gas increases. With a good sector management the price decreases and the number of consumers who ask for disconnections from the gas system also decreases,” says Dana Dunel senior partner at Bostina, Buzaianu and Associates and a lawyer specialized in utility companies.

GAS MAKE - UP

The Romanian natural gas market is made up of the following:

Producers: SNGN Romgaz SA, SNP Petrom, Amromco Energy and L.LC. New York.

Storage system operators: SNGN Romgaz SA and SC Depomures SA.

Distributors: SC Distrigaz Sud SA, SC Distrigaz Nord SA, SNP Petrom S.A., SC Congaz SA.

Suppliers: SC Distrigaz Sud SA, SC Distrigaz Nord SA, SNTGN Transgaz SA, SNP Petrom SA, SNGN Romgaz SA, SC Congaz SA, Amromco Energy, L.LC. New York, SC Depomures SA.

Transit system operators: SNTGN Transgaz SA.

Importers: SC Distrigaz Sud SA, SC Distrigaz Nord SA, Termoelectrica, Wirom.

|

|

Shut out of reform

Racism has forced the Rroma to the margins of Romanian society, with experts sadly admitting that the situation for the minority was better under Ceausescu. Special report by Ana-Maria Smadeanu. Pictures by Eric Roset Racism has forced the Rroma to the margins of Romanian society, with experts sadly admitting that the situation for the minority was better under Ceausescu. Special report by Ana-Maria Smadeanu. Pictures by Eric Roset

Twenty kilometers northwest of Bucharest two villages lie side by side, representing the extremities of rich and poor.

Bolintin Vale and Bolintin Deal rest in the industrial heartland of the south. Deal resembles one of the more upmarket districts of Bucharest. Pretty, newly-painted villas sporting the latest fashion in colours, bright oranges and yellows demonstrate a wealth few Romanians can aspire to. Here there are not many houses without a BMW or Audi in the driveway. The gardens are large, the homeowners are smartly-dressed. Their wealth has come from the men who work abroad in construction, mostly in Italy and Spain or are 'lautari', Rroma singers. The women remain at home, taking care of the housework. In this village no one is registered as a Rroma. They all define themselves as Romanians.

Although Deal does not look like a stereotypical Rroma neighborhood, with its pointed roved-houses, where the women wear traditional skirts and headscarves, the citizens' professions, such as singers, give an insight into their heritage.

The mayor Emilian Banica of the town and representatives of the community invite our group, including state secretary and president of the National Agency for Rroma Ilie Dinca, into their house, where we accept the invitation of a 'lautari' to play for us. There the hospitality is accelerated as we are given Lavazza coffee, a premium brand few in Bucharest can afford. The mayor Emilian Banica of the town and representatives of the community invite our group, including state secretary and president of the National Agency for Rroma Ilie Dinca, into their house, where we accept the invitation of a 'lautari' to play for us. There the hospitality is accelerated as we are given Lavazza coffee, a premium brand few in Bucharest can afford.

But in the garden an argument breaks out between Dinca and a local man. The subject concerns a violent attack from an Easter night 14 years previously. A young student from Deal refused to give a lift to a young Rroma man. Angered, the Rroma turned on the driver and stabbed him to death. Members of the neighbourhood then turned on the murderer, burnt down his house and sent him and his family into exile from the town. Dinca is attempting to reintegrate the family into the community, but the citizens reject the idea, frightened that their serenity will be upset.

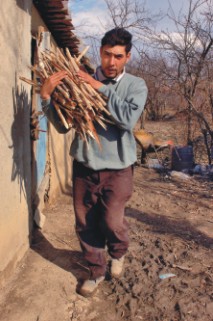

In the nearby town of Vale the situation is different. Here the buildings are dull, falling down and showing signs of neglect. The people dress in traditional Rroma attire, the women in colourful handmade clothing and the men in black Stetson hats. Many of the people here have not left to work abroad, instead they travel with a horse and cart from city to city collecting scrap metal and empty bottles, which they sell on for tiny deposits. In the local high school, only one child graduated in a year. Of the six thousand people here, 1,800 are registered as Rroma.

This illustrates that once Rroma have reached a certain state of affluence or, one could say, when they have moved from the Vale to the Deal, they often choose not to register themselves as Rroma.

Because the Rroma lack a nation and a strong voice it is almost seen as acceptable, even in polite society, to ridicule the Rroma. European-wide they have become “the minority it is okay to hate”. Officially Romania has 533,712 registered Rroma. This is the number of people who chose to describe themselves under this ethnic identity. But conservative estimates put the number of those of Rroma descent at two million, around ten per cent of Romania's population.

“Why would they assume an identity as long as this description represents a danger for them?” says Costel Bercus, president of an NGO that represents Rroma, Romani Criss. “Why would they assume an identity as long as this description represents a danger for them?” says Costel Bercus, president of an NGO that represents Rroma, Romani Criss.

“It does not work for you to be a gypsy in Romania today,” adds Roxana Marin, a teacher and campaigner for Rroma rights. “They are the appendices of society.”

There are few, if any, Rroma role models who 'come out' in politics or business. Those who the public suspects of holding a Rroma past are evasive about their background. Only in entertainment, such as among musical stars that are popular in Rroma communities, are there figures who celebrate their roots.

“They come to perceive it as a disadvantage, if they trumpet it too loudly,” says Marin.

According to Bercus, the Ardeal in Transylvania is the most populous Rroma area, but they are resident all around the country.

“The same thing is true of the Rroma, they have the right to choose if they want to keep their identity or not. Some Rroma do not want to be called 'Rroma' and they have that right as long as they live in the majority's culture, speak Romanian, have been educated like the Romanians and have nothing to do with Rroma culture,” adds Bercus.

The ones who do not mind being called 'tigani' (gypsy) have lost the connection with their culture, he believes. This is because the word 'Tigani' does not exist in the Rroma language and they have become used to other countries imposing this insult upon them. For a comparison, think of French people being quite content to call each other by the vulgar phrase 'Frogs'.

Many Romanians argue that the Rroma population does not want to integrate into the nation's society. “When a lot of Romanians talk about integration, they mean assimilation,” says Roxana Marin. “For them, integration means giving up traditions and acting like Romanians. That's not going to happen.” she says.

But Bercus argues that some pragmatics have to be expected, and many do not feel proud to be Rroma.

“They have the right of assimilation and not to suffer discrimination,” says Bercus.

Romanians also have a palpable fear of Rroma. But much of this is due to financial problems. Some homeowners are frightened that if they live in a gypsy district or move to an area where gypsies live, the value of their house will fall. When visiting a flat to buy or rent a landlord will frequently say: “This is a great neighbourhood, there are no gypsies here.”

Other districts, such as allegedly Olt, encourage people not to register themselves as Rroma, so they can argue to the authorities they have 'gypsy-free' districts. Also in Sfantu Gheorghe, in a neighbourhood called Orko, where 1,800 Rroma live, the situation seems close to apartheid. There is no water, gas or electricity and between the Romanian neighbourhood and traditional Rroma is a wire fence that separates the two communities.

“I haven't seen such a thing in my life,” says Elena Cruceru the president of the PER (Project on Ethnic Relations) office in Romania. “Everything is at the lowest poverty level.” There is, however, a social assistance centre run by a Rroma leader, a medical centre, dentist and a school. That centre has arranged for the population to have access to ID cards.

However this atmosphere seems to set up only two choices: assimilate or stay a victim.

CO-EXISTENCE LESS THAN SMOOTH

In the 1970s, every morning before Roxana Marin went to school, her grandmother would braid her hair with the red, yellow and blue colours of the Romanian flag, to help her make a better impression on the Romanian children. But at school this kids still used to tease her and pull her hair. This taught Roxana to be assertive. In the 1970s, every morning before Roxana Marin went to school, her grandmother would braid her hair with the red, yellow and blue colours of the Romanian flag, to help her make a better impression on the Romanian children. But at school this kids still used to tease her and pull her hair. This taught Roxana to be assertive.

One afternoon she cracked open her wooden pencil case on the head of a boy, causing him to put his head in a bandage for a week.

The problem of discrimination, she argues, exists from both sides, with Rroma children indoctrinated to not look too kindly on their Romanian neighbours.

“I was taught at a young age that I can't trust Romanians, that they will cheat me. That they are mean,” says Marin.

One of the pillars of the European Union's ideology is a fair representation of minorities. But Rroma leaders and citizens agree that the situation under Ceausescu was better for the minority than the last 15 years.

“Many Rroma had security because the discrimination was not so visible, although it did exist,” says Bercus.

“Access was more equal. It was more controlling, but less indiscriminate. Of course, there was discrimination,” says Ciprian Necula, coordinator for minority programs at the Monitoring Media Agency.

“In Ceausescu's time, if a Rroma who applied for a job was rejected on the discrimination criteria and he made a complaint to the authorities the next day, the Rroma would be hired. Today the authorities apply penalties, but the Rroma are still disproportionately unemployed,” Necula adds.

Therefore many Rroma suppress their background in order to apply for jobs. “This pushes the categories of Rroma to the margins of society,” says Marin.

However, during the Communist period the Rroma were forced to assimilate by the Party during the period 1970 to 1977.

“They didn't have the right to travel and were forced to lose their ethnic identity, but from the social, economic point of view it was better. There was the same pretext of stability for everyone,” says Necula.

Martin supports this view. “Children were often put on the desk at the back of the class. But kids had to go to school and stick with it, or the inspectors would check up on their parents and they would face a fine.”

LACK OF ACCESS

Now many Rroma do not have the same access to health, education, jobs and housing as Romanians. Even as consumers they are kept out. There is a strategy used by shops and bars that is accompanied by a panel behind the till that reads: 'We are allowed to choose our customers'. This means that Rroma are often not served with goods or drinks.

“From the point of view of access, the situation has got worse in the last fifteen years,” says Marin. Necula adds: “Until 2002 there was a visible discrimination of the Rroma. Even in classified job adverts it was written: 'We are hiring a supervisor, Rroma excluded [exclus rom]' and that affected the minority.”

But when Rroma are hired, they are often the first to be fired.

There is also a vicious circle concerning having access to identification. Many Rroma have neither birth certificate, ID card nor 'Buletin' and because of this a lot of Rroma kids do not go to school. Nobody then hires them without a diploma.

Rroma find it hard to gain identification because they do not have a 'fixed abode' or place to live. Often they stay in shacks on the edge of town. These homes are unauthorised. If they have neither ID nor birth certificate, they cannot get access to mortgages, bank credits or credit for home appliances or cars. They have no legal status, cannot get immunisations or legal employment. Many do not know how to apply for free health insurance. However, many doctors refuse to register Rroma at their surgery. They often agree to register their children, but not the adults. This creates an underclass that is driven into illegal activity, which can cause future problems for the country.

“If the authorities made sure that everyone had an ID, many of these problems would be sold and it would ease the burden on the state,” says Marin.

Many schools will not accept children registered as Rroma. There is also segregation in the classroom. Recent Government moves led to Rroma culture, history and language classes being taught separately from the Romanian children. The problem is that these classes are often given in the worst room in the school, sometimes in the basement. “Under the pretext that the kids are too noisy,” says Marin.

This encourages the most talented Rroma kids not to register in the school under that description. Therefore, from the first grade, the brightest deny their background in order to get ahead.

THINGS HAVE ONLY

GOT WORSE

Recently history includes the burning of villages and forced migration. Around 1999 the ministry of the interior undertook an operation, 'Luna', to rid Bucharest of the ‘mizeria societatii’ (the filth of society). The ministry scoured the streets and the makeshift houses, evicting the prostitutes, Rroma and homeless. Then they bussed them to the outside of Bucharest, on the Pitesti highway, and prevented them from entering the capital.

It was not until 2001 that the Government of Romania adopted a strategy for the Rroma minority. But this was not efficient, due to a lack of money. There are some great intentions, but without finance success is impossible. And with affluent Rroma integrating into the community and 'turning Romanian', the minority lacks a Ion Tiriac to act as a lighting rod for investment and international appeal.

The Romanian Government has given money to several organizations that belong to national minorities and are represented in the National Council for the Minorities (an organisation that participates in the elections). But again finance is a problem. 85 per cent of the money that the Rroma Partied, representative of the minorities, receives from the Government is spent on administrative costs such as salaries and rents, according to Bercus.

He says that finance should be available for the promotion of minority culture, different activities for youth and stimulation to the Rroma to participate more in the life of the local community.

The European Union has appointed the first Rroma minister to the European Parliament, Hungarian of Rroma descent Livia Jaroka, which is the first step to greater representation. There are also many NGOs working on Rroma issues and EU funds available to the community. These look good on paper, but much of the money is not absorbed by the most needful. In education, PER conduct intensive programs in Romania to revise history textbooks in order to include coverage of country's minorities. In collaboration with Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), PER is formulating policy recommendations for the Government.

As an NGO, Romani Criss was set up in the context of interethnic conflicts, which included the burning down of Rroma villages between 1990 and 1996, with an aim to prevent troubles between the Rroma and the local communities, including the Hungarians. The organisation interferes in conflict situations and often ensures legal representation for Rroma who have been wronged. As an NGO, Romani Criss was set up in the context of interethnic conflicts, which included the burning down of Rroma villages between 1990 and 1996, with an aim to prevent troubles between the Rroma and the local communities, including the Hungarians. The organisation interferes in conflict situations and often ensures legal representation for Rroma who have been wronged.

Romani Criss involves different communities in school, health and labour force programmes. The finance sources for Romani Criss are various. They don't work with Romanian Government money. “From the beginning we maintained our independence by not becoming the Government's customer,” says Bercus. The money for the NGOs comes from Norwegian, Great British and German Governments, from OSCE, European Council, European Commission and private donations from abroad.

Some of its programmes fail, especially those that try to raise the community from poverty.

“Romania is in a market development stage,” says Bercus, “and has become competitive. The traditional professions of the Rromas have no place.”

There are around 20 different sociological categories of Rroma, divided by their jobs. For example 'caldarari', who make cutlery and kitchenware from aluminium, also 'ursari' who train bears, 'rudari' who are expert in woodcraft and 'lautari' - musicians. These skills will be passed down through generations in a similar manner to medieval guilds. Each community has varying degrees of engagement with their Rroma identity and some, such as the 'lautari', become extremely wealthy.

The Rroma have the right to maintain their traditional culture, argues Bercus, and this must be protected. He compares this situation with that of authentic Romanian peasant villages.

But Bercus is worried that they are not transforming their traditional jobs into ones that modern society demands and needs.

There are exceptions, such as a printing house in Ialomita which is turning a profit, a farm in Constanta and an arable community in Bacau, where the citizens use agricultural equipment supplied by Romani Criss.

But facing the challenges of a twenty-first century market economy is not a task the Romanians or the Rroma have yet managed to achieve.

A HISTORY OF OPPRESSION

Romani tribes are thought to have emigrated from the Indian sub-continent to Europe one thousand years ago. For five hundred years until the end of the 19th century, Rroma in Romania were slaves, either for the King, church or for private owners. They maintained jobs such as tool-makers, weapons manufacturers and entertainers. Only a small minority were nomadic. Even these travellers only tended to migrate from district to district or over the borders in cycles of three months. The notion that all Rroma are a solitary crowd, travelling in carriages, and keeping to themselves, is mythic.

In the holocaust, the Axis powers sent around 1.5 million Rroma to their deaths. Although this had been a forgotten tragedy for many years following the end of the conflict, now it seems that in some quarters this is viewed as a second-class massacre. The most expansive Holocaust memorial, the recently erected Monument to the Murdered Jews of Europe, which takes the form of 2,700 stone slabs in the centre of Berlin, did not acknowledge the Rroma disaster.

Rroma history is one of oppression from state authorities of all shades and persuasions. This has contributed to disenfranchisement from society.

“Because the system didn't care about them, they didn't care about the system,” says Roxana Marin, a teacher and campaigner for Rroma rights.

Now there are estimated to be around 12 million of Romani descent in the world.

WHAT'S IN A NAME?

There has been much discussion on the description for the minority. The dilemma between whether to use 'Romani', 'Rroma' or 'Tigani' (gypsy) started in 1995, when the then Minister of Internal Affairs Teodor Melescanu sent a memorandum to all state institutions not to use the 'Roma' to define the minority, but instead 'tigani' because of the former's confusion with the word 'Romanian' in the international language. Rroma groups protested and, in 2000, the Government agreed to use the word 'Rroma'. This was partly because, between 1995 and 2000 some organizations agreed to write the word with double 'r' to avoid the confusion with 'Romanians'. There has been much discussion on the description for the minority. The dilemma between whether to use 'Romani', 'Rroma' or 'Tigani' (gypsy) started in 1995, when the then Minister of Internal Affairs Teodor Melescanu sent a memorandum to all state institutions not to use the 'Roma' to define the minority, but instead 'tigani' because of the former's confusion with the word 'Romanian' in the international language. Rroma groups protested and, in 2000, the Government agreed to use the word 'Rroma'. This was partly because, between 1995 and 2000 some organizations agreed to write the word with double 'r' to avoid the confusion with 'Romanians'.

The word 'tigani' doesn't exist in the Romani language. There is some debate over the origins of the word 'tigani'. In the past, etymologists believed it came from 'Egyptian' as this was the country where some communities believed the Rroma originated from. But Romanian Rroma groups say the word comes from the Greek word 'atinganoi' which means 'untouchable'. Because communities saw the Rroma as a travelling community, they were not seen as untouchable, or difficult to get to know.

|

|